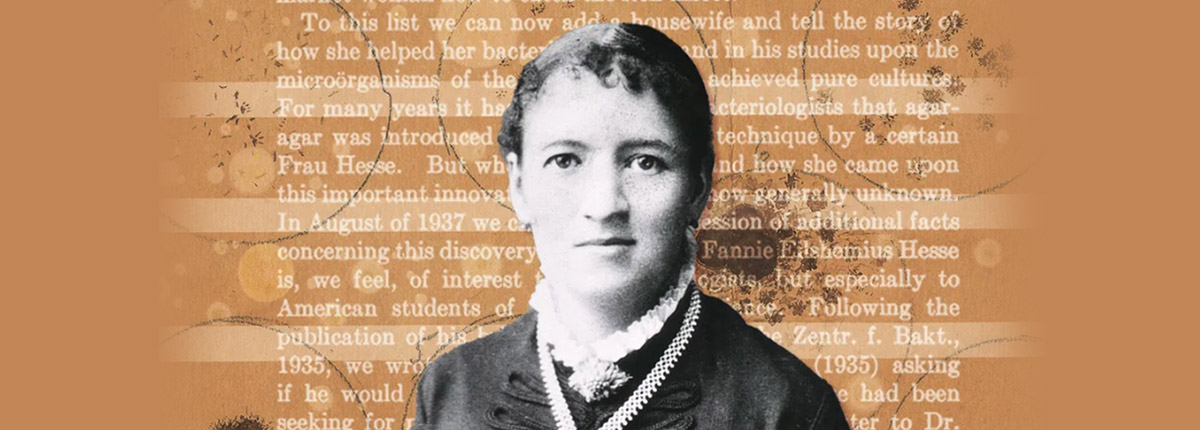

The secret revolutionary

Lina Hesse and the invention of microbiological agar cultures.

Who would have thought that the true story of the microbiology revolution would only now come to light?

Probably not even Fanny Angelina Hesse, who revolutionised microbiology with the idea of using a simple culinary gelling agent to cultivate microorganisms. Her suggestion, in 1881, to use agar as an alternative to gelatine as a culture medium helped her husband Walther and Robert Koch to research diseases such as tuberculosis. Although agar became indispensable in scientific research, Hesse’s contribution went largely unappreciated as neither she nor her husband officially documented their discovery.

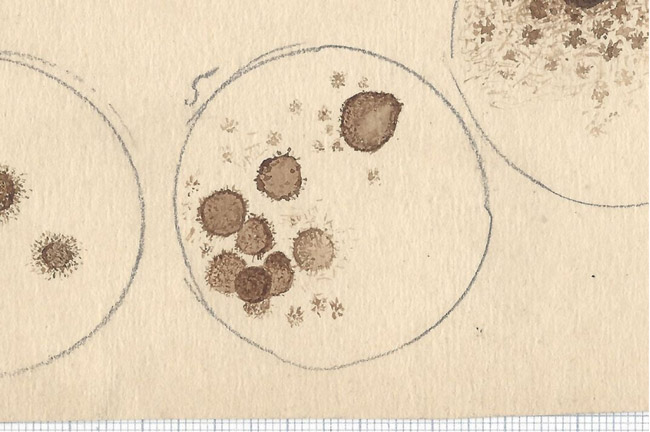

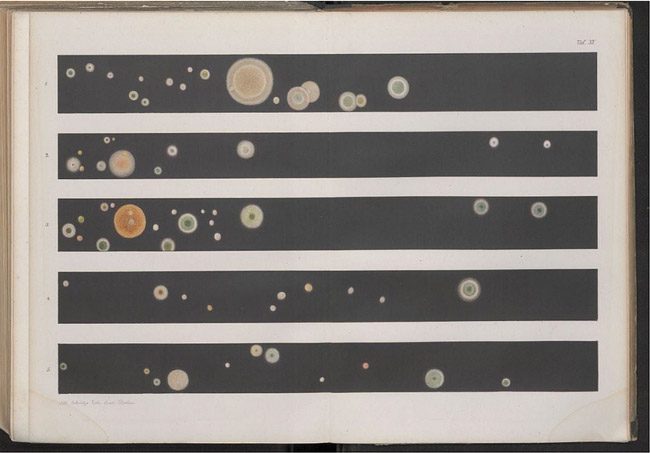

When studying microorganisms in laboratories, scientists often use a somewhat surprising medium: agar, a gelatinous substance that, when mixed with other nutrients, promotes the growth of bacteria and similar small organisms. Typically, the bacteria are then cultivated in round Petri dishes in a nutrient medium mixed with agar – with the lid facing downwards so that condensation water can collect there.

But agar has not always been used for this purpose. Before the late 19th century, it was mainly used as an ingredient in desserts and soups. At that time, researchers lacked a method to grow microorganisms (also known as microbes) as pure cultures isolated from other species – a crucial step towards finding a cure for the diseases caused by these organisms. Solid substances such as potato slices and coagulated egg white had several disadvantages, above all their strong turbidity. While gelatine offered some advantages, it was easily consumed by microbes and melted at the high temperatures required to cultivate bacteria. By adding agar to a nutrient-rich mixture, these problems were avoided and a transparent growth medium was created that could not be degraded by the bacteria.

The introduction of agar into the life sciences dates back to a hot summer’s day in 1881, when Fanny Angelina Hesse, known to her family as Lina, suggested an unexpected substitute for the gelatine her husband Walther was using to study microbes in the air. An article from 1939 states: “The unbearable liquefaction of the gelatine ruined many of the experiments, and finally [Walther] began to look for new solidifying agents”. Lina suggested agar, “which she had used for years in her kitchen to make fruit and vegetable jelly”.

Agar is the culture medium on which microbes grow and become visible without a microscope. These tiny organisms were first observed in 1674, when the Dutch merchant and self-taught scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovered “little animals” in plaque scraped from his tooth. “There are more living animals in the impure matter in the teeth of your own mouth than people in an entire kingdom”, he explained after looking at the sample under a rudimentary microscope. But seeing is not the same as understanding. Until the early 1880s, physicians hotly debated whether microbes could cause disease or whether they were merely by-products of diseased cell tissue.

According to Wolfgang’s 1992 biography, Lina was Walther’s “most important supporter in many different projects”, making drawings of microscopic samples for her husband’s published work and assisting him in the laboratory. In the summer of 1881, Walther, who was trying to study microbes in the air, was frustrated by the gelatine with which the glass tubes in his laboratory were coated. “One day [he] asked Lina why her jellies and puddings remained firm at these temperatures”, wrote Wolfgang. “She told him about agar-agar”. Agar was stable at high temperatures, resistant to decomposition and easy to sterilize and store over long periods of time. This made it possible to create long-term cultures in which microbes could multiply under controlled conditions, facilitating their analysis.

Walther Hesse sent a letter with the details of his discovery to Robert Koch, who was trying to determine the cause of tuberculosis, an infectious disease that killed around one in seven of those infected in Germany at the time. On 24th March 1882, Koch gave a widely acclaimed lecture in which he proved that tuberculosis is caused by a bacterium, thus paving the way for better diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

In popular accounts of the history of microbiology, Koch is sometimes credited with the first use of agar in laboratories. For example, the Nobel Prize website states that the scientist has “invented new methods … for cultivating pure bacterial cultures on solid culture media such as potatoes and agar”. In his 1882 lecture, Koch made reference to the role of agar in the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but failed to acknowledge the Hesses’ contribution to his research. The Hesses themselves never wrote a report on agar, which could explain why their names are practically unknown today. “In the Hesse family, this contribution to bacteriology was hardly ever mentioned”, writes Wolfgang. “Lina never talked about it, probably because she was a very modest person”.

Although Koch made the applications of agar known, he did not immediately recognise its superiority as a microbial growth medium. For years, scientists (including Walther) debated the advantages of gelatine over agar.

Lina Hesse was born Fanny Angelina Eilshemius in New York on 22nd June 1850. Her father was a wealthy Dutch merchant who immigrated to the United States as a young man, while her mother, a cousin of the Swiss painter Louis Léopold Robert, was born in Lugano.

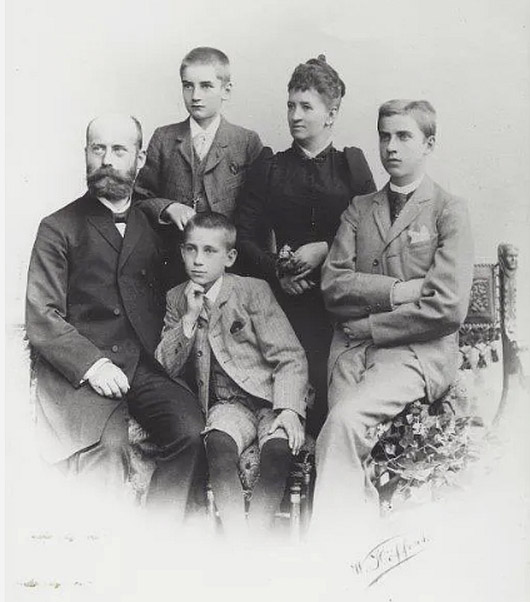

Lina’s parents married in 1849 and had ten children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Lina was the eldest of the siblings. Artistic talent ran in the family: she followed in the footsteps of her second cousin, who produced scientific illustrations, while her brother Louis Michel Eilshemius was a successful painter in New York City.

Although the family lived in the USA, they had strong ties to Europe. After the turmoil of the Civil War, wealthy Americans often visited Europe in the summer months, with Germany – in particular the city of Dresden, sometimes referred to as “Florence on the Elbe” – proving to be a popular destination. In September 1865, at the age of 15, Lina was sent to a girls’ boarding school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, to learn French, housekeeping and etiquette, as was customary for young upper class women of the time.

At home in the USA, the family knew the German doctor Richard Hesse, who had moved to Brooklyn to practise medicine. Richard Hesse introduced the Eilshemiuses to his brother Walther, who lived in Dresden and had worked as a doctor on a German ship travelling to and from New York in the winter of 1872 and 1873.

Following their introduction in New York, Walther and Lina met again in Dresden. The couple married in Geneva in 1874 and then settled in the German state of Saxony. They were united by a common concern – the desire to understand the invisible forces that make people ill.

As district doctor in the town of Schwarzenberg near Dresden, Walther investigated the mysterious lung disease from which the workers in the nearby silver, cobalt and uraninite mines suffered. Two decades before the discovery of radium by Marie Curie in 1898, radioactivity and its harmful effects on health were still barely known. Instead, Walther focused his attention on hygiene and dirt particles in the air.

To further his research, Walther studied under the hygienist Max von Pettenkofer in Munich in 1878 and 1879. He then worked for the Berlin bacteriologist Robert Koch, who advised him on microbial research in the early 1880s. It was the latter, long-lasting medical interest of Walther’s that brought the power of agar – and Lina’s insight – to full fruition.

“Berlin was the Mecca of medical research in the 1880s”, says Benjamin Kuntz, Director of the museum at the Robert Koch Institute. “When Walther came to his laboratory, Koch was an unknown doctor who had just set up as a young scientist. The house where Koch and Walther worked is still standing”.

Lina Hesse died in December 1934, 23 years after her husband, who had passed away in July 1911.

Source: